I originally intended to blog about each city I visited during this vacation in Hong Kong & mainland China, but I got so busy with the actual tourism that I didn’t end up writing anything except for Hong Kong.

However, recent experiences flying (first from Xi’an to Shanghai Pudong, and then from Beijing to my birthplace) have been sufficiently dissatisfactory to warrant a rant about the state of domestic air travel in China.

1. China Southern Airlines problems

Supposedly this is one of the 10 worst airlines in the world, according to Business Insider/Zagat.

Xi’an to Shanghai

Our flight from Xi’an to Shanghai was delayed by about 3 hours. The incoming flight was late supposedly due to weather in Shanghai, so it wasn’t necessarily the airline’s fault. However, communication about the matter was rather poor (see complaints below about the XIY airport) and the delay estimates didn’t seem to be updated in the airline’s electronic systems, even though they knew pretty early on that our flight wouldn’t be able to leave til nearly midnight. China Southern’s website, Google, and (I think) FlightAware, were all providing inaccurate information as a consequence.

Meanwhile, multiple other airlines seemed to have no problem getting planes to fly the same route on time.

Beijing to my hometown

The flight left on time.

Curious observation, not so much a complaint: why did they think it necessary to serve food on a 1.5 hour short haul flight that left at 11 pm? It was a sausage bun of the sort you’d find at an Asian bakery for very cheap… not that one should expect very much of economy class airline food.

I did have an issue with the no mobile phone policy; mobile phone use is prohibited, even in airplane mode. Supposedly this is a Chinese government regulation for which foreigners have been detained for violating. I’m sure older planes with unshielded wiring could be affected by the cumulative effects of everyone’s EM interference—and that’s probably part of why China’s rules haven’t caught up to Europe’s or the US’s—but I really doubt the A320 would have faced much risk from smartphones in airplane mode. A flight attendant actually came around to enforce the rule. Oh well. I suppose we’ll have to blame the government for this obsolete rule.

2. Airport problems

Xi’an Xianyang International Airport (XIY)

The airport was grand and modern—far bigger than was necessary given the remoteness of and air traffic to that city. When we arrived from Hong Kong by Dragonair, we were basically the only arriving international flight; all the other gates seemed to be empty, and our flight’s baggage came on the only active conveyor belt, right next to a sign with such bad Engrish that it substituted an f for what have been a t in “tag”.

The departure hall, too, was much bigger than this city needed. There were other more serious problems, though.

For one, the technology seemed to outpace the capabilities of the people—a recurring observation on this trip. Airport employees made simultaneous, overlapping announcements on the PA system, talking over each other. They also made that gross blowing sound into the microphone each time before starting an announcement, as a mic check. For comparison, I’m told that at many Western airports, announcements are recorded and placed into an automated, prioritized queue (e.g. see Phonetica).

Second, the departure hall featured at least one smoking chamber. The one I observed was a glass booth for people to smoke their cigarettes… but the glass walls didn’t reach the floor, so the booth wasn’t actually isolated from the surrounding environment. Smokers also didn’t close the door fully, which led to that entire gate area smelling like smoke, unfortunately triggering my asthmatic cough repeatedly for those three hours we were delayed there.

Third, there was a ridiculous lack of use of digital information systems. The counter at the gate where we were waiting appeared to lack an airline reservations/logistics computer, and delays were usually not reflected on the airport displays, instead being announced in Chinese and broken Engrish on the PA. On the counter hung a piece of paper, hand-filled with the flight number and the fact that there was a delay. Eventually when we boarded, I don’t even recall if our tickets were scanned—just checked by the gate agent a flight attendant at the gate.

Whatever illusions of modernity and professionalism one got from the physical appearance of the airport were disrupted by these oversights.

Beijing Capital International Airport (PEK) Terminal 2

Never mind that Terminal 2 (T2) and Terminal 3 (T3) are practically separate airports with a minimum connection time (MCT) of 160 minutes for domestic<->international connections… or that the Airport Express train only goes from T3->T2 and not the other way around…

Possibly because of the passenger load at PEK, the airline would not accept checked baggage prior to 3 hours before departure. Consequently, I could not go through security, and had to lug around my heavy suitcase to coffee and dinner in the unsecured area for a few hours… while coping with the dearth of general (i.e. not paid restaurant) seating space prior to security. While I was sipping my drink, I began wheezing and coughing—remember my allergy-related cough?—because some unscrupulous customers were smoking, indoors, in an open restaurant. I can’t believe no one else complained. At last, a waitress told the smoker to put it out.

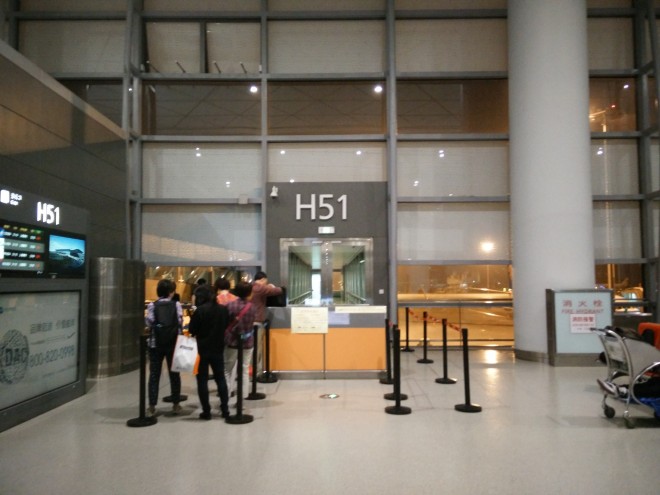

The story doesn’t get much better after screening. Once inside, I found that my boarding pass did not indicate a gate, and that the terminal displays did not show a gate assignment. My impression, and I could be wrong, is that PEK—and perhaps other airports—does not assign gates until shortly before departure. Unfortunately, that also meant no clear direction to go in the secured area, and nowhere really to sit…

Well, hey, at least I got to charge my phone at a charging station… which other patrons seemed to treat as a garbage bin in table form.

3. The alternative: high speed rail

High speed rail in China is a wonderful thing. We took it from Shanghai to Nanjing in 2nd class, and from Nanjing to Beijing in 1st class seats. In each segment, top speeds exceeded 300 km/h. Trains always left and arrived on time, and seats were more spacious than any economy class seats on an airplane. Typically trains run about every 15 minutes along this route, and all the ones we took on this trip seemed to be filled.

Here are some photos of Chinese high speed rail stations and trains, from my last visit in 2012:

Given that a trip from Shanghai to Beijing in 2nd class would only be 553 RMB (about $89 USD)—uniform pricing regardless of when the ticket is purchased, unlike airfare—and that train stations are generally more convenient to get to/from than airports are—where a high speed rail link exists, I would definitely choose it.

4. Is it any better in the US?

I don’t fly that much in the US, and when I do, it’s often a rather short flight between Philadelphia and Boston. JetBlue and American are pretty nice, though. Even then, the convenience of taking Amtrak to/from 30th Station in Philadelphia and South Station in Boston usually makes rail travel far preferable to short haul flights when rail is an option.

But I doubt the US will ever develop high speed rail as China has. There’s not enough space or money or will—and, arguably, there is no comparable need.

Do you have comparable complaints about domestic air travel in China or the US? Please share.